In golfing terms, Melbourne truly ranks with the greatest of destinations – and it sometimes takes an outsider, or a bunch of them, to remind us of that.

There are swathes of short grass across the layout, so much so that the average golfer will rarely lose a ball, but what the better player will discover is how they have to identify the right positions amid all this space, and how often the best path to the hole is indirect. Play conservatively, and par or bogey is always within reach, but anything better requires thought and ambition – a risk-reward equation that is pure Mackenzie. The rise and fall of the wide fairways, temptingly short par-fives and speedy, sloping greens all evoke Augusta. The comparison between the two Mackenzie creations is so common it’s hackneyed, but it’s hard to shake the similarity when walking the ground at Royal Melbourne, even though the low-lying ti-tree gives off quite a different ambience to the tall pines of Georgia.

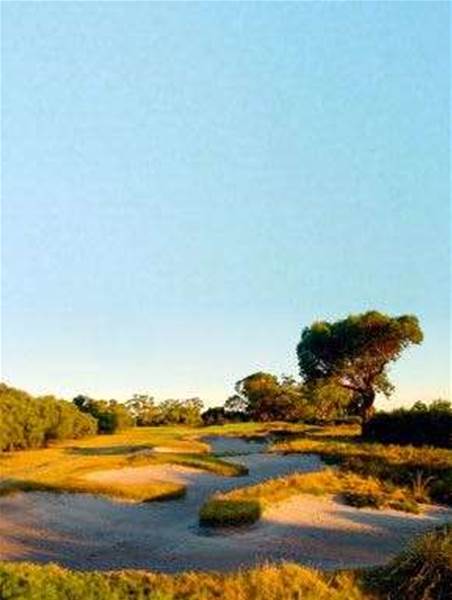

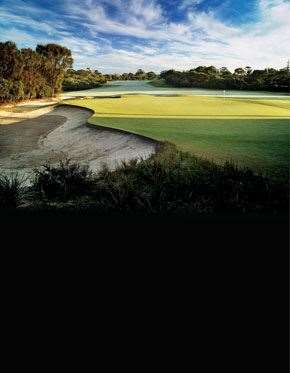

Royal Melbourne’s 9th hole, is a brilliant stretch.

Royal Melbourne’s 9th hole, is a brilliant stretch.Images: Victoria Tourism

Every opportunity to play a great, historic course is to follow in the footsteps of the game’s greats, but part of the mystique of Royal Melbourne is visitors don’t quite get to play the course that the pros do. The club has 36 holes between its West and East courses, but when the stars of the tour come to play, they go out on an 18-hole amalgam known as the Composite course. Formulated in 1959 when the club hosted what is now the World Cup, its purpose was practical – it kept the layout entirely within the main property, sparing spectators from having to cross to the holes on the other side of the road, which is a public thoroughfare.

There’s perpetual debate in the various rankings of Australian courses about whether to consider the Composite – Inside Sport's sister publication Golf Australia does not – because it’s a course that, in a sense, doesn’t really exist for people to play. The argument deepens with this Presidents Cup, as Royal Melbourne has come up with a new configuration (it also did this in 1998), begging the question: is it a tweaked Composite, or a new course? The basic structure remains – 12 holes from the West, six from the East – but the East’s par-3 16th has been brought in for the first time to serve as hole no.14. The front nine is still sheer, unalloyed brilliance, from the opening short par-4, with all kinds of dynamism packed into its 304 metres, to the awe-inspiring green site of the 4th, to the 6th, another short par-4 imprinted on the memory of your correspondent, because it was here during a practice round at the ’98 Cup that I almost got plinked on the head twice by drives from Ernie Els and Nick Price.

Literally over the fence from Royal is Victoria Golf Club, host of the most recent Australian Masters and another of the Sandbelt’s gilt-edged names. It, too, can hang the “Mackenzie was here” sign on the door, but has its own famous personages to deploy. Just through the driveway, there appears a statue of club member Peter Thomson. On its base is inscribed the outline of five claret jugs and five years, tribute to Thomson’s prolific haul of Open Championship victories.

It’s rather fitting that the nation’s most accomplished major winner sets the scene at Victoria, which has the reputation of being the player’s club of the Sandbelt. It owns the most wins in the state’s notoriously competitive inter-club pennant competition, which dates back to 1899. In addition to Thomson, Geoff Ogilvy is on the club’s rolls, as are younger tour professionals such as Matthew Griffin, one of the contenders at last year’s Australia PGA, who was at the course working on his game the day we turned up for our visit.

Walking around the clubhouse, Victoria’s pride in its great achievers is evident. A room is named for Thomson and Doug Bachli, another favourite son who won the British Amateur in 1954. The outdoor terrace is named for Ogilvy. Old clubs, medals and trophies abound, as well as one photo which is a more recent addition. Perhaps the club’s proudest moment of all was in 1954, when Thomson and Bachli held the trophies for Britain’s grand old championships, which sat side-by-side on the mantle in Victoria’s clubhouse. “No one thought to take a photo,” the club’s general manager, Peter Stackpole, says. But last year, the Amateur title was won by a Melbourne-based Korean Jin Jeong, while the Open’s Claret Jug was in town for the major championship’s qualifying event held at Kingston Heath. “I pinched the trophies for an afternoon and we were able to re-create the photo,” says Stackpole.

To be called a player’s club often implies having a difficult course, one that can challenge elite-level talent. Victoria, instead, is a high example of the Sandbelt’s playable-over-penal qualities. It’s not long - under 6,300 metres from the tips - and made even shorter in typically firm-and-fast conditions. The 1st has been properly described by player-turned-architect Mike Clayton, who has worked on Victoria over the past decade, as one of the more unusual starts to a round. At 233 metres, it’s much too short for a par-4, but not really a par-3, particularly with its angled green and front-left bunker. Many will make par or better here, but the demands immediately escalate at the ensuing pair of long par-4s. Victoria also carries on the old-school practice of visitor accommodation in the clubhouse. There’s probably no more central place to stay in the Sandbelt, as the other pocket of great courses lies 10 minutes’ drive away, where Kingston Heath is found.

Related Articles

Lightning and low rounds at NSW Women’s Open

"More pointless than Pokémon": Tomorrow's Golf League critiqued, and roughly