In golfing terms, Melbourne truly ranks with the greatest of destinations – and it sometimes takes an outsider, or a bunch of them, to remind us of that.

In golfing terms, Melbourne truly ranks with the greatest of destinations – and it sometimes takes an outsider, or a bunch of them, to remind us of that.

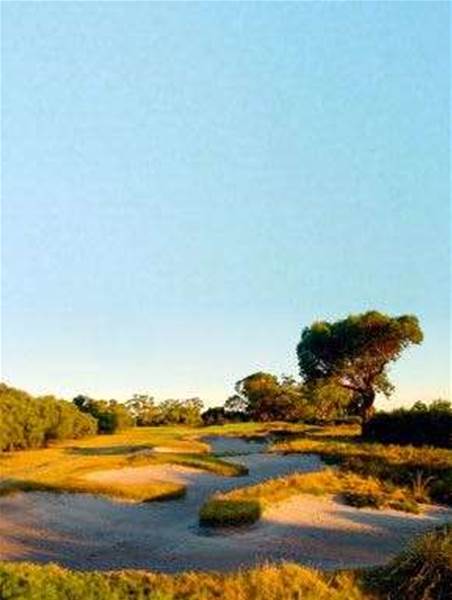

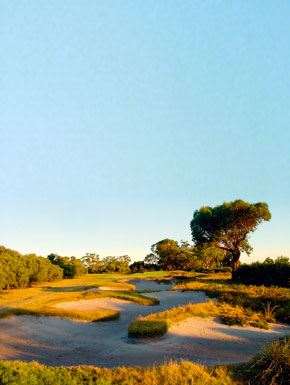

Kingston Heath’s par-3 15th.

Kingston Heath’s par-3 15th.Images: Tourism Victoria

As the golf correspondent for the Associated Press, Doug Ferguson is on the ground at more tournaments during the year than anyone else in the press corps - and many of the players, for that matter.Always identifiable inside the ropes for his Hawaiian shirts, he’s a fixture of the pro tour, someone who’s seen plenty of the golfing landscape, and every airport, hotel and rental-car depot in between.Two year ago, he tracked Tiger Woods on his long-awaited return to Melbourne for the Australian Masters at Kingston Heath. Eager to pick Ferguson’s brain, I asked him about the places he had travelled to for golf. He brought up a defunct tour event in a remote part of rural Georgia, where, the story goes, American star Davis Love showed up for his tee time with eye black still on his face, having spent the morning hunting. He mentioned how it always amazed him that the British could take the Open Championship to tiny seaside towns and run the event beautifully. With an upcoming US Open at Pebble Beach, he talked of how excited he was at getting to spend another working week on the glitzy Monterey Peninsula.

And what was the best? Ferguson had anticipated the question. “I know I’m not catering to your audience,” he replied, thinking that I expected him to name-drop some far-flung locality in California or the Carolinas, Scotland or Ireland, for Southern Hemisphere travellers to dream about. “But it’s here. Melbourne.”Ferguson might have been engaging in golf’s customary politesse to that week’s host, but there’s reason to believe he was being sincere. In golfing terms, Melbourne truly ranks with the greatest of destinations – and it sometimes takes an outsider, or a bunch of them, to remind us of that. The Presidents Cup, the biennial team competition that pits the United States against the rest-of-the-world outside of Europe, will turn the attention of the golf world to the Royal Melbourne Golf Club later this year, following on its first visit in 1998. The visitors will gush, as the course remains by far the best the Cup has ever played.It might be a case of familiarity breeding contempt, or a simple matter of taking things for granted. In Victorian tourism circles, the old trope goes that Melbourne has to invest in events because it has no Harbour Bridge or Barrier Reef, no great “assets” either man-made or natural. In the context of golf, nothing could be further from the truth – the courses of the Sandbelt, the stretch of land in the city’s suburban south-east, are esteemed in the rather esoteric field of golf architecture for how they balance their ingenious design with an authentic naturalism. These courses bear an unmistakable stamp – where many new layouts in Asia or the Middle East look like they were air-dropped in from the US, the Sandbelt’s tracks take on the character of their setting, another quality which sets them apart on the global scale.

They also have the benefit of being associated with perhaps the greatest golf course architect in history. Much as Gaudi pervades the shape of Barcelona, or Frank Lloyd Wright is inseparable from Chicago, golf in Melbourne is indelibly linked to Alister Mackenzie. The Scottish doctor, designer of Augusta National and Cypress Point among others, was brought out to Australia by Royal Melbourne in 1926 to work on their course. Few other seven-week periods in golf history could be rivalled for productivity, as Mackenzie not only consulted on Royal Melbourne but 18 other courses around the country, and almost all of the leading clubs of the Sandbelt (Royal earned a commission on the extra work it found for him, and ended up making a profit on his trip).

The sum of Mackenzie’s efforts was a lasting influence that would, pardon the pun, change the course of Australian golf. There is debate about how much credit is paid to him – for one, Mackenzie never saw his work finished – over his equally important local collaborators, the Australian Amateur champion Alex Russell and Royal Melbourne superintendent Mick Morcom. But with the way they carried forth Mackenzie’s design precepts, it can be properly said that course architecture in Australia can draw a dividing line at what was done before the doctor’s visit and after it.

Mackenzie’s plan for the routing of Royal Melbourne’s West course sits in a frame on the wall of the general manager’s office at the club. There are minor differences to the course in the ground today, but the flow of the holes, with the brief interlude on the back nine that crosses over the road, is unmistakable. If you think of a golf course as a movie, then the routing is the script, the thing that draws together the individual characters and plot points into a coherent whole. Royal’s script is seamless from the opening hole, whose unmissably wide fairway sounds the first note of what is to come.

There are swathes of short grass across the layout, so much so that the average golfer will rarely lose a ball, but what the better player will discover is how they have to identify the right positions amid all this space, and how often the best path to the hole is indirect. Play conservatively, and par or bogey is always within reach, but anything better requires thought and ambition – a risk-reward equation that is pure Mackenzie. The rise and fall of the wide fairways, temptingly short par-fives and speedy, sloping greens all evoke Augusta. The comparison between the two Mackenzie creations is so common it’s hackneyed, but it’s hard to shake the similarity when walking the ground at Royal Melbourne, even though the low-lying ti-tree gives off quite a different ambience to the tall pines of Georgia.

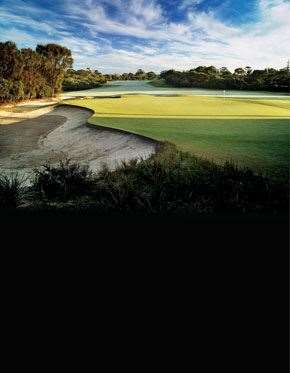

Royal Melbourne’s 9th hole, is a brilliant stretch.

Royal Melbourne’s 9th hole, is a brilliant stretch.Images: Victoria Tourism

Every opportunity to play a great, historic course is to follow in the footsteps of the game’s greats, but part of the mystique of Royal Melbourne is visitors don’t quite get to play the course that the pros do. The club has 36 holes between its West and East courses, but when the stars of the tour come to play, they go out on an 18-hole amalgam known as the Composite course. Formulated in 1959 when the club hosted what is now the World Cup, its purpose was practical – it kept the layout entirely within the main property, sparing spectators from having to cross to the holes on the other side of the road, which is a public thoroughfare.

There’s perpetual debate in the various rankings of Australian courses about whether to consider the Composite – Inside Sport's sister publication Golf Australia does not – because it’s a course that, in a sense, doesn’t really exist for people to play. The argument deepens with this Presidents Cup, as Royal Melbourne has come up with a new configuration (it also did this in 1998), begging the question: is it a tweaked Composite, or a new course? The basic structure remains – 12 holes from the West, six from the East – but the East’s par-3 16th has been brought in for the first time to serve as hole no.14. The front nine is still sheer, unalloyed brilliance, from the opening short par-4, with all kinds of dynamism packed into its 304 metres, to the awe-inspiring green site of the 4th, to the 6th, another short par-4 imprinted on the memory of your correspondent, because it was here during a practice round at the ’98 Cup that I almost got plinked on the head twice by drives from Ernie Els and Nick Price.

Literally over the fence from Royal is Victoria Golf Club, host of the most recent Australian Masters and another of the Sandbelt’s gilt-edged names. It, too, can hang the “Mackenzie was here” sign on the door, but has its own famous personages to deploy. Just through the driveway, there appears a statue of club member Peter Thomson. On its base is inscribed the outline of five claret jugs and five years, tribute to Thomson’s prolific haul of Open Championship victories.

It’s rather fitting that the nation’s most accomplished major winner sets the scene at Victoria, which has the reputation of being the player’s club of the Sandbelt. It owns the most wins in the state’s notoriously competitive inter-club pennant competition, which dates back to 1899. In addition to Thomson, Geoff Ogilvy is on the club’s rolls, as are younger tour professionals such as Matthew Griffin, one of the contenders at last year’s Australia PGA, who was at the course working on his game the day we turned up for our visit.

Walking around the clubhouse, Victoria’s pride in its great achievers is evident. A room is named for Thomson and Doug Bachli, another favourite son who won the British Amateur in 1954. The outdoor terrace is named for Ogilvy. Old clubs, medals and trophies abound, as well as one photo which is a more recent addition. Perhaps the club’s proudest moment of all was in 1954, when Thomson and Bachli held the trophies for Britain’s grand old championships, which sat side-by-side on the mantle in Victoria’s clubhouse. “No one thought to take a photo,” the club’s general manager, Peter Stackpole, says. But last year, the Amateur title was won by a Melbourne-based Korean Jin Jeong, while the Open’s Claret Jug was in town for the major championship’s qualifying event held at Kingston Heath. “I pinched the trophies for an afternoon and we were able to re-create the photo,” says Stackpole.

To be called a player’s club often implies having a difficult course, one that can challenge elite-level talent. Victoria, instead, is a high example of the Sandbelt’s playable-over-penal qualities. It’s not long - under 6,300 metres from the tips - and made even shorter in typically firm-and-fast conditions. The 1st has been properly described by player-turned-architect Mike Clayton, who has worked on Victoria over the past decade, as one of the more unusual starts to a round. At 233 metres, it’s much too short for a par-4, but not really a par-3, particularly with its angled green and front-left bunker. Many will make par or better here, but the demands immediately escalate at the ensuing pair of long par-4s. Victoria also carries on the old-school practice of visitor accommodation in the clubhouse. There’s probably no more central place to stay in the Sandbelt, as the other pocket of great courses lies 10 minutes’ drive away, where Kingston Heath is found.

If Royal Melbourne is the undisputed greatest hit of the Sandbelt, the Heath is the cool No.2 beloved by connoisseurs. It’s easy to admire Royal for its grand sweep; what golfers appreciate about Kingston Heath is how such a small, relatively flat piece of land can produce such a great layout.

Melbourne hosts for a second time, former players Fred Couples and Greg Norman back as team captains.

Melbourne hosts for a second time, former players Fred Couples and Greg Norman back as team captains.Images: Victoria Tourism

In the earlier context of routing as film script, Kingston Heath is a terse thriller, full of short, sharp and unexpected turns. Having visited the course on two previous occasions for professional tournaments, the way the sequence of holes flowed from the green to the next tee still came as a surprise. The Heath’s bunkering, another Mackenzie product, is the attribute that earns the most notice, but the routing was the work of Dan Soutar, an expat Scot who was among Australia’s first great competitive golfers. The way the course moves from short to long holes provides an utterly complete test of shot-making.

Those bunkers, though, cannot be ignored. It’s somewhat weird for a golfer to think of a hazard in affectionate terms, but the swirling shapes and sharp edges of the Heath’s bunkers have an undeniable artfulness to them. They’re the best example of Sandbelt bunkering, the distinctive style envied all over the world. There’s a notion that such bunkers are only possible in the unique ground of the Sandbelt, although that’s refuted by course architects and builders.

Mackenzie left his mark in the sand at the Heath, and one awesome hole. His 15th is perhaps the best par-3 in Australia, the kind of hole you spend the entire front nine looking forward to. By the time you reach this hole, you’ve already played another great par-3, the pint-sized 10th, and the 5th is a tremendous one-shotter that’s somehow only the third-best on the course. The 15th plays uphill – a rarity among great par-3s – a mere 140 metres, but to a green with yawning bunkers either side. The slope on the putting surface is near funhouse, particularly if the putt is from above the hole.

The 15th leads to a great closing run of holes: the par-4 16th, with its blind drive and double green it shares with the 8th, to the long par-4 17th, which winds its way uphill to its tilted saucer of a green, then the finisher, another long par-4 to test the golfer to the line, with a tough green that presently holds the distinction of being the last one that Tiger walked off in victory. Right after my round at the Heath, I learn that Woods’ potential return to Melbourne for the Presidents Cup has been clouded by injury – a shame for him, no doubt, because he has to travel a long way to play golf like this.

– Jeff Centenera

The author travelled to Melbourne as a guest of The Presidents Cup 2011. Presidents Cup Travel still has several travel packages to the event this November including tickets, golf and accommodation (1300 300 756,

www.thepresidentscuptravel.com

Related Articles

Lightning and low rounds at NSW Women’s Open

"More pointless than Pokémon": Tomorrow's Golf League critiqued, and roughly