It’s commonplace and often a little frustrating that we have a tendency to assign the moniker of ‘legend’ or ‘great’ far too casually these days.

Sustaining a purple of patch of success over a year or two in any aspect of life can be enough nowadays for many to wax lyrically, often without suitable reference to history or past achievement.

The term ‘GOAT’ – ‘Greatest of All Time’ – is an even more recent mantle often associated with a current Australian cricketing off spinner and in our game, also applied with reference to Tiger Woods on a frequent basis. One wonders if Woods is familiar with the term, let alone his own thoughts on the matter.

The only other candidate to unseat Woods as the ‘GOAT’ turned 80 years of age in January. For an increasing number of fans of the game, footage of his play in his prime is the closest they’ll get although we’re still blessed to be able to watch him perform first tee duties at The Masters and appear in the annual Father and Son gathering, partnered with an ever rotating series of sons and grandsons.

Jack Nicklaus’ record and the incredible tenure of a career that began professionally in 1962 and saw him win his 18th major championship 24 years later, is worthy of all of these monikers and more. If not for Woods, he’d be without question the lone ‘GOAT’ in the conversation.

Ask anyone for their most treasured Nicklaus memory and it’s that final major, the 1986 Masters at age 46, that is spoken of with great reverence. Catching and passing younger tyros that included Norman, Ballesteros, Watson and Kite with a stunning 65 is on the shortlist of the most memorable championships in the game’s history.

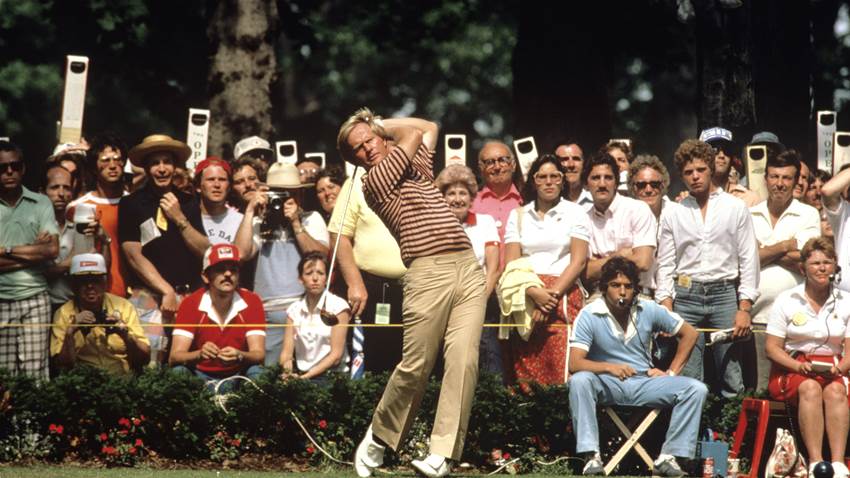

RIGHT: Nicklaus drives during the 1980 US Open at Baltusrol in New Jersey. PHOTO: Getty Images.

If not for that win however, an argument could be made for Nicklaus’ performance in winning TWO majors in 1980, starting with the U.S. Open at Baltusrol and backed up with a dominant PGA Championship victory two months later, as perhaps his most significant achievement given the circumstances at that stage of his career.

If you weren’t around to watch these performances unfold – and let’s face it, if you lived in this part of the world and are under age 50, you probably didn’t – Nicklaus’ performance at Baltusrol to win the Open over a dogged Isao Aoki of Japan was like watching the world’s biggest rock star making a return after years in retirement.

You might have caught up on this binge-watching old footage during our COVID-19 lockdown but after winning at least once annually since his debut year, the Golden Bear provided evidence that he was human by enduring the first winless year of his career in 1979. And for the most part, he wasn’t close to contending and had slipped to a completely unfamiliar position as an also ran on the season’s money list.

Tom Watson had surpassed him as the World No.1 player and the precociously talented Seve Ballesteros was capturing the world’s attention and opening his majors account at the 1979 Open and 1980 Masters. Around the bar at the 19th and in magazine pages the world over, many were quick to surmise that Nicklaus was not only past his best but being unceremoniously nudged into the background by these emerging superstars.

"First, it irritates you, then it really bothers you, until finally you get to damn blasted mad at yourself that you decide to do something about it. I've decided to do something. And I will. Or I'll quit." - Jack Nicklaus in March 1980.

Juggling family and his blossoming ‘Golden Bear’ business ventures seemed to be taking a toll and Nicklaus had cut back on an already lean schedule of appearances to around a dozen per year to retain his hunger for the game, only adding fuel to the fire of criticism that he wasn’t playing anywhere near enough to remain competitive. It seems the critics weren’t alone, however.

"I'm sick of playing lousy. I've just been going through the motions for two years," Nicklaus said in a Washington Post article in March 1980.

"First, it irritates you, then it really bothers you, until finally you get to damn blasted mad at yourself that you decide to do something about it.

"I've decided to do something. And I will. Or I'll quit."

40 years is a long time ago but let’s pause to reflect on the landscape of international golf coverage at the time of the 1980 U.S. Open, well before the internet, social media and mobile devices that allow for coverage and content to be pumped to us from every corner of the globe, every Tour, every week.

Switch on our flat screens and we have tournament action beamed to us, entire channels dedicated to golf, highlight packages, historic features, instruction pieces.

Back in 1980, there were just five TV channels in Australia and live coverage of the majors, maybe the old World Matchplay at Wentworth and some Pro Celebrity golf filmed in Gleneagles, Scotland, was close to the limit of international coverage available at the time. If you wanted updates on any sports scores in those days, calling a recorded phone line listed in the front of the White Pages was your best opportunity prior to the newspapers being published the next day.

"The scoreboard at the 18th screamed ‘Jack is Back’ and that outpouring of elation and relief was shared with an eruption of excitement from the galleries and loungerooms around the world."

Unless you’d been there, nobody knew what the first five holes at Augusta National looked like as The Masters coverage only kicked in from the 6th hole. Mention the term ‘podcast’ and something to do with fishing might have sprung to mind and the PGA Tour itself might as well have been on the moon if you lived outside the United States.

Any live coverage of Nicklaus, Watson, Ballesteros or Lee Trevino therefore, was a rare event and certainly worth setting the alarm for.

Nicklaus hadn’t started 1980 in much better fashion and in fact, had missed the cut in Atlanta the week before the U.S. Open. On paper, hardly the shot of confidence the 40-year old might have hoped for but he’d only entered on a whim as he was excited to test a putting tip in competition that long-time mentor Jack Grout had given him weeks earlier.

A second round 67 in Atlanta ensured he was in high spirits as he left for Baltusrol in suburban New Jersey, already a venue exuding positive vibes for Nicklaus as the site of his 1967 Open victory. Nicklaus did better than bring his Friday form from Atlanta to town too, an opening seven-under 63 marked his best-ever start in a major championship and was sweet music to the ears of the game’s administrators and supporters.

Like Woods today, Nicklaus was the man who most ‘moved the needle’ in terms of global interest in the game. Surely his slumping fortunes over the previous 18 months had the then PGA Tour Commissioner Deane Beman at least at little concerned, even if he didn’t care to admit it publicly? Beman after all, had fought tooth and nail to increase the profile of the Tour that at the time he took over as Commissioner in 1974, had lagged behind bowling in terms of TV ratings and contract values.

Like Woods today, Nicklaus was the man who most ‘moved the needle’ in terms of global interest in the game. Surely his slumping fortunes over the previous 18 months had the then PGA Tour Commissioner Deane Beman at least at little concerned, even if he didn’t care to admit it publicly? Beman after all, had fought tooth and nail to increase the profile of the Tour that at the time he took over as Commissioner in 1974, had lagged behind bowling in terms of TV ratings and contract values.

RIGHT: Japan's Isao Aoki pushed Nicklaus all the way before the American claimed his 16th major championship. PHOTO: Steve Powell/Getty Images.

“No.” Beman countered matter of factly when I asked if he recalled harbouring concerns about Nicklaus. “I never had any doubts about Jack's capabilities as he was the ultimate competitor.”

Incredibly, that 63 was only good enough to share the lead alongside long-time combatant Tom Weiskopf. While Weiskopf couldn’t sustain his bright start, Nicklaus’ competitive hard wiring, improved fundamentals and a short game radically overhauled in the previous months under the tutelage of long-time friend and former Tour player Phil Rodgers, kept Nicklaus in the lead through Saturday evening.

A three-putt par on the 18th on Saturday would haver left a bitter taste as it meant forfeiting the outright lead and a share with Aoki at six-under, a shot ahead of Lon Hinkle and by two over a trio that included the dangerous Watson.

For the fourth straight day, he and Aoki would be paired together and try as he might as the final round progressed, the vastly more experienced Nicklaus could not shake the idiosyncratic Japanese tyro.

"How times have changed. Can you imagine anyone rushing the green from behind the ropes to get within arm’s length of a player on a putting green these days?"

The pair jockeyed back and forth in a pure matchplay battle and it was not until the 17th green when Nicklaus dramatically rode home a 25-foot birdie putt that he could breathe a little easier. However, the two-stroke lead was nearly erased a few minutes later when Aoki almost holed his pitch from the rough on the 18th, before Nicklaus eventually sealed it with an 8-footer for birdie.

The scoreboard at the 18th screamed ‘Jack is Back’ and that outpouring of elation and relief was shared with an eruption of excitement from the galleries and loungerooms around the world.

How times have changed. Can you imagine anyone rushing the green from behind the ropes to get within arm’s length of a player on a putting green these days? That was the case at this moment, causing Nicklaus to bottle his immediate elation to turn traffic cop in an attempt to halt the masses from trampling not only himself but Aoki, who still faced had his short putt to complete his championship.

Those final green scenes would today feature on the Tour’s security training video espousing ‘what not to do’ but such was the excitement generated by Nicklaus, the same player galleries loved to hate when he first came out on Tour to rival the much beloved Arnold Palmer as the game’s best.

Jack, most certainly, ‘was’ back and two months later, he underlined he return with a final day romp to win his 17th Major and fifth PGA Championship at Oak Hill Country Club in New York State.

Into his 40s and on that same limited schedule, Nicklaus managed to raise his game to threaten for his 18th and final Major on more occasions – most notably the ’82 U.S. Open loss to Tom Watson at Pebble Beach and the ’83 PGA Championship – before that unexpected but thoroughly memorable triumph at Augusta in 1986.

These were halcyon times indeed and the legend has continued to burn bright in the years since he passed on the torch to others and closed the book on his competitive days.

To borrow that modern term, Jack is for many ‘the’ GOAT.

Then and Now.

Related Articles

Scottie Scheffler joins Tiger Woods in rarefied air

Nicklaus, Watson cast doubt on any PGA-LIV merger