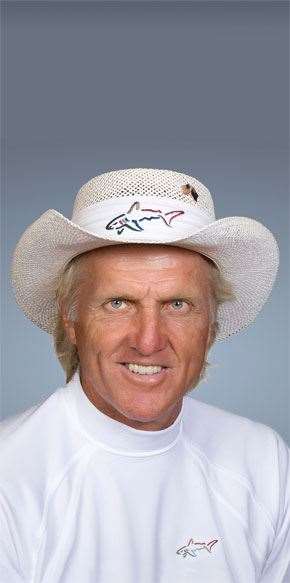

Greg Norman – if he isn’t already – will soon be known more as a brand than a champion golfer. Fine by him …

Greg Norman – if he isn’t already – will soon be known more as a brand than a champion golfer. Fine by him …

Greg Norman Golf

Greg Norman GolfImages: Getty images

Your columnist was recently witness to the spectacle that occurs when Greg Norman makes one of his periodic returns to his country of origin. On a schedule akin to that of a head of state, Norman visited his ongoing golf course works in three states, spruiked for the Australian Open in Sydney and generally served in his role as the nation’s golfing avatar. But the visit wasn’t all bathed in iconic glow – Norman was dogged by questions about the closure of his course design office in Sydney and a corresponding opening of a new office in China. Certain quarters of the media pounced on the move as a sign of Norman diluting his ties to Australia.

Norman described it as a business consolidation, but the corporate-speak could hardly convey the fierceness with which he defended the move. His reasoning was perfectly valid – the great share of future golf course work is in Asia, and separate to that, he still has a host of business interests in Australia – but plainly a nerve had been struck. Any notion that the Shark, or more accurately his brand, was somehow less authentically Australian seemed to incense him. The Aussie factor remains an important part of the image he projects, particularly as his work goes global.

The Norman brand has reached an interesting moment as it continues the transition from post-playing career extracurricular to thoroughgoing concern. When the question was put to him that his legacy in golf may eventually be more for what he did after the two Majors and 86 other tournament victories, his grin betrayed not a hint of ex-player nostalgia. “Great. Doesn’t bother me at all.”

It’s perhaps a prerequisite attitude for the business of Norman to survive beyond its golfing connotations. Another recent journey within the golf industry, to an event held by apparel brand Lacoste, cast this thought in an interesting light. The Lacoste name now stands for itself in fashion, inspiring immediate associations of crocodiles on brightly coloured polo shirts. But the name originated with Rene Lacoste, who was by some measures the best tennis player of his day, a winner of seven Grand Slam singles titles in the 1920s. His legacy, however, is surely for founding La Societe Chemise Lacoste and the shirt he wore while playing – the rare athlete-endorser to have created a lasting brand.

It’s an oblique reminder of how quickly athletic glory can fade for even the greats. When Marcus Jordan tweeted during the NBA Finals that no one should ever compare Kobe Bryant to his father, Jordan younger certainly wasn’t wrong, but instead irrelevant. To walk through a Nike store and see the products of the Jordan brand and its familiar Jumpman hanging docile behind the display windows full of the latest shoes that Bryant or Lebron James are wearing, is to be reminded of a figure that has not been surpassed, only superseded.

Michael Jordan’s ability to move units was unquestionable, but we’re seeing how it was tied to his specific greatness as a player. As the endpoint of David Beckham’s career approaches, encapsulated by his presence on England’s bench at the World Cup, his durability as a marketing phenomenon will be an interesting case study. Trying to transcend his own sporting greatness is the main game for Greg Norman right now, and it’s as challenging as trying to win a British Open in your mid-50s. In whatever tennis pantheon exists out there, Rene Lacoste is looking down and smiling like a crocodile on a shirt.

– Jeff Centenera

Related Articles

Lightning and low rounds at NSW Women’s Open

"More pointless than Pokémon": Tomorrow's Golf League critiqued, and roughly