Epic run in the Majors confirms arrival of a new superstar.

In a recent interview with an American golf magazine, the comedian Larry David picked out the only thing that Jordan Spieth has to worry about. Trust the creator of Curb Your Enthusiasm and the man who inspired the character of Seinfeld’s George Costanza to see it. “He’s going to be a bald man; he’s going to be wildly bald,” David said of Spieth, and one can only wish that he did it in the voice he used for his old Steinbrenner impersonation on the show. “It’s one thing to handle the pressure of the back nine at Augusta; let’s see how he does when he sees all that hair in the tub. That’s pressure.”

When asked about the comment, Spieth’s reply was as perfect as one of his pitch shots: “That’s pretty funny. Nothing I can do about it.” And that’s how it is for Jordan Spieth during this career moment, in which he handles everything that comes at him on and off the course with supreme aplomb. His 2015 wasn’t merely “good”, and “great” doesn’t cut it as a description either. It was straight-up historic, the kind of season even the game’s most honoured legends would’ve been thrilled to bank.

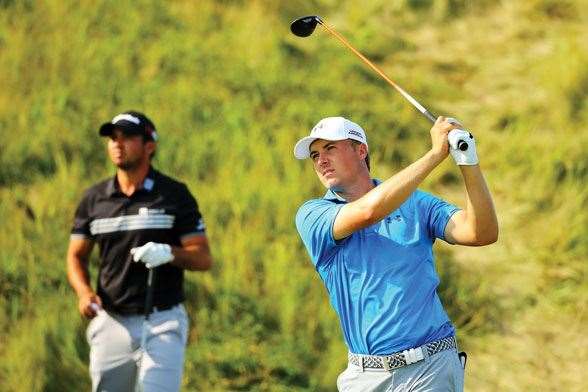

In dominating the Masters last April, then emerging from the morass of the US Open in June, Spieth arrived at the Open Championship in July as only the sixth golfer to have won the first two legs of the modern calendar Grand Slam. But for a fickle bit of Friday weather at St Andrews, which landed Spieth a single shot outside the three-man play-off, his chance at the Slam might have been live heading to the PGA. And there, Jason Day had to pull off his own record-breaking performance just to deny Spieth a third Major for the year.

The raw finishes said enough: win-win-tied fourth-second. As modern-Major years go, only Hogan’s 1953 (three wins from three; he didn’t play the PGA) and Woods’ 2000 (fifth at the Masters, then swept the rest) were clearly superior. By the imperfect measure of total score in relation to par, Spieth’s 2015 was the finest, his 54-under across the four events one better than Woods’ former record. Fittingly, Spieth became the 18th man to claim the mantle }of world no.1 (only to lose it again – more about that later). And as he only turned 22 at mid-year, he dialled up age-related milestones with each success, often finding that the only pro golfer who did it better younger was a certain Nike-clad prodigy.

While Spieth matched or invoked Woods’ feats and similarly spiked excitement levels within American golf, there was a different atmosphere around the new guy. Spieth is not quite the anti-Tiger, but there were some distinct contrasts. Woods was an exotic creature coming from beyond golf’s established realm, a 21st-Century athlete who could do things other golfers simply could not. Spieth, however, cut such a classic figure that he verged on archetype. His golf is not game-changing, nor does it ooze technical or stylistic perfection; rather, he happens to play a familiar game very well. Spieth is from Texas, Dallas to be more precise, and the inheritance of that golfing heartland seemingly courses through him. The Hall of Fame golf writer Dan Jenkins, another son of the Lone Star State, paid Spieth the highest of compliments by describing him as an amalgam of the perfect Texas golfer: “The will and focus of Ben Hogan, the likability of Byron Nelson and the putting stroke of Ben Crenshaw”.

For a noted curmudgeon like Jenkins to gush was really saying something, but his reaction was hardly exceptional. The golf press collectively swooned. Perhaps it was a corrective to years of tense stand-off with an unknowable Tiger, but the hacks were utterly taken by Spieth’s affability, his respectful manner and his willingness to share something more than arcane swing thoughts. This was best captured in a piece by Bryan Curtis for the Grantland website, where he wrote: “Part of what makes Spieth likable is that he’s great. It’s more profitable to cover greatness ... But there’s also a moral component of Spieth love – the notion that reporters have discovered that rarest of birds, the nice-guy superstar.”

The golf subculture, which jealously tends to its particular etiquette and standard of behaviour, is relishing the emergence of Spieth as a defining player of the era. In organisational lingo, he’s an ideal cultural fit. There’s no celebrity pretension here – when avid golfer Caitlyn Jenner tried to set Spieth up with model-daughter Kendall, Spieth politely declined, citing he didn’t know who she was (of course, he’s still with his high-school sweetheart). In Jordan Spieth’s model-golfer existence, even the premature baldness can be made into a positive, relatable attribute. Larry David wasn’t insulting him when he pointed it out: “This makes him way more appealing to me.”

The receding hairline is certainly not a sign of stress. Instead, it might be the marker of Jordan Spieth’s most admired attribute – an old head on young shoulders. He indeed has a near-ideal golfing mentality: competitive yet composed, gutsy while guileful. Tour sage Geoff Ogilvy compared him to Bernhard Langer, the paragon of calm on the links, while Crenshaw reached for an historical figure: the gunslinger Wyatt Earp.

Spieth’s introduction to the wider golf world was telling. In 2010, the 16-year-old received an offer to play in his hometown PGA Tour event, Byron Nelson’s old tournament, the kind of feel-good amateur invitation that will draw a few more locals outside the ropes for the two rounds before the cut. But the schoolboy became the story of the week in finishing 16th (and overshadowing the first-time PGA Tour winner, which just happened to be Day). Spieth was invited back the next year, and made the cut again.

The biggest impression Spieth made was how perfectly at ease he looked on the most strived-for circuit in the golf world. Turning pro in late 2012, he claimed a PGA Tour victory in his rookie season and became the first teen to get a win on the tour in more than 80 years. Just about his only letdown came at Augusta 2014 when Bubba Watson overhauled him in the final round.

Spieth’s mental-game mastery at such a young age is impressive, and points to a new kind of golf-development paradigm. Tiger’s emergence at the turn of the century augured a new class of physically gifted talents formerly found in other sports, instead raised monomaniacally from a young age with a club in their hand. The image of slouchy touring pro with the baggy shirts and pants would be obliterated. Athletes would rule golf, the kind resembling the likes of American bomber Dustin Johnson.

Golf’s precocity records have been knocked over with regularity over the past 20 years, but not quite for the reasons that were predicted. The new class of golfing champion doesn’t wow with athletic ability, but rather an overall soundness to their games that encompasses their mental approach. It has empowered them to aim high, and quickly. Spieth is their symbol; on the ladies’ tour, it would be New Zealand wunderkind and newly minted Major winner Lydia Ko, while closer to home, Cameron Smith and Minjee Lee are this type of prospect.

It’s not like the kids have suddenly become mentally tougher. On the contrary, according to former Golf Australia national squad coach and author of the book Iron Golf Mind, Peter Knight. He sees more mental fragility than ever, just as it is with young people facing similar pressures. “I think there’s opportunities now to develop mental skills more quickly – and that comes from the development of everything,” he says.

“From a technical aspect, if a player wants to swing the club better, it’s like, ‘How do you prove it to me?’ You can actually measure improvement much more readily than what we could, so the player goes, ‘Hey, I feel like I’m hitting the ball better, but I can see that I am. The numbers and the video show it, therefore I know I’m on the right track. Hey, I’ve got a lot of confidence in what I’m doing.’ Therefore, all of the mental skills are going to be better-placed. It’s hard to separate them out.”

Compared to previous generations, junior golfers have benefitted from the spread of expertise and competitive opportunities. They are able to prepare in a tour-like way long before they ever cash a tournament cheque. Knight raises the example of his trips to Taiwan, where he works with junior players, and is asked the same question every time he goes there. “Why are the Koreans so good?” he laughs.

Korea indeed is near mass-producing such complete players on the women’s side. “Partly it’s a numbers game; lot of players getting into the game younger, the information they’re getting is better,” Knight says. “There’s also the ‘he or she did it at whatever age, so why can’t I?’”

As Spieth claimed a stunning victory at the US Open at Chambers Bay, it was also the breakout moment of another 21-year-old in Cameron Smith. A Queenslander, like his famed namesake, Smith was playing his first Major. To the chagrin of Aussie golf fans, the rookie barely registered on American TV coverage – even to the point when he hit the shot of the tournament, a 260m approach to the par-5 last which rolled to tap-in eagle range. Smith tied for fourth, a finish that secured his spots on the PGA Tour and at the first two Majors next year.

His coach, Grant Field, was following on Twitter back in Queensland. “I read he had hit a good drive. They shot to [playing partner] Louis Oosthuizen hitting his third shot to the green, and as the ball lands, I see a marker a foot from the hole. Then my phone went berserk.”

Field started coaching a ten-year-old Smith, who went on to win everything significant at the amateur level in Australia. He prides himself on Smith’s self-sufficiency. “With Cam, we created a lot of systems early on,” Field says. “He didn't have to relearn that when he turned pro. For a lot of them, it’s almost like you have to fail first and find your way. Now, they’re so much better-organised when they’re younger. They transfer it from junior to amateur to professional golf.”

The product is a bunch of young golfers who play without fear. Field notes that quality in Smith, and also credits his family background. “His parents were great. If Cam played bad, there were no repercussions. It was never about him being a tour player. I know [his father] Des always said if he never did anything in golf, the experiences that he had were more important ... He’s never been worried about performing well or poorly. A lot of guys are scared to play bad, but also to play well.”

This is a familiar-sounding story. Spieth’s background has been well-noted – he’s worked with the same coach, a Texas-based Aussie expat named Cameron McCormick, since he was 12. Together, they’ve crafted a method that hasn’t come from the junior-golf cookie-cutter approach – Spieth has an unusual grip and a bent left arm – that is highly effective. He owns his game.

Spieth’s family life is also notable. His family is sporty – his father played baseball and mother and brother played basketball – and golf was just another sport. Another facet of his upbringing is his younger sister Ellie, who has special needs. Spieth has spoken of how her circumstances have kept him grounded, in that he’s never been the centre of attention in his own family.

Whether such young players are raised to have better mental games, or rather have some innate skill at it, invites nature vs nurture questions. Knight notes that it’s always a combination of both, but adds the idea that when it comes to the sporting mindset, it’s about assigning meaning. “Look at someone like Spieth, or Jason Day. Jason’s story is one of hardship. You sort of think: all these players come up with excuses all the time for ‘why I can’t’. Whereas the ones who succeed go ‘I don’t care about that, this is why I can’. And it’s a totally different attitudinal placement.

“As humans, we are meaning-makers ... You look at athletes who had family tragedy and then reach great heights, because it’s ‘I’m going to perform for them’. Whereas another athlete might withdraw. It could be the same type of event, but the meaning made of it is different.”

This calls to mind the goings-on at the US Open. With many in the field complaining about the course at Chambers Bay, a new championship venue, there were a lot of excuses rattling around players’ heads. Spieth, who almost lost the title after a double bogey on the 17th, before recovering to birdie the last and watch Johnson’s three-putt help his cause, was implacable. “Someone has to win it. The quicker you realise that and don’t worry about it, the easier it is just to move on with your game and that’s what

we try to do.”

In what became something of a press conference in-joke during the year, thanks mainly to the efforts of the Aussie golf media’s man on the US tour, AAP correspondent Ben Everill, Jordan Spieth has talked a lot about the significance of his victory at the 2014 Australian Open. There it was again after the Masters: “That could arguably be one of the best wins that I’ve ever had – I would obviously call this one the greatest wins I’ve ever had, no offence,” as the assembled writers broke out in laughter.

But what Spieth did at The Australian shouldn’t be undersold. Like it was for Rory McIlroy the year before, the Australian Open proved to be a welcome tonic. Spieth hadn’t won in calendar 2014 even while piling up eight top-ten finishes, and there were more than a few instances where he looked shaky in and around the lead. On a tough, gusty Sunday, he shot a clinical 63 to blow away the field by six shots. Big-name rivals were left in his wake; McIlroy shot 76, while Adam Scott managed 71.

“What the Australian Open did is, in a period where I had some struggles towards the top of the leaderboard on Sundays, it was a level of patience and a level of ... it was trial and error for a couple of times and I had not found the solution,” Spieth said at the Masters. “We had not found the solution as a team and we found the solution in Australia against a world-class field including the world no.1 and 2 at the time. Closing out that tournament and seeing what that meant in the history of that tournament and understanding who won there, it meant a lot.”

After claiming the Stonehaven Cup last November, Spieth quipped that he hoped he could have the kind of follow-up year that McIlroy had after his Aussie win. In emulating the Irishman with a pair of Major wins and a stint at the top of the rankings, Spieth set up the next dominant narrative arc in golf. With Jason Day’s victory at the PGA, the storyline became even richer. As it looks ahead to 2016, the game is buzzing about a new prospect (and we’re not talking the Olympics) – an honest-to-goodness big-three rivalry.

In what often seems to happen in golf, the end of Major championship play for the year happened just at the moment when matters were getting really interesting. In September, the top spot in the world rankings bobbled about like a putt on a spiky green. While it reflected an objective confusion about who was no.1, it certainly was a bad look for the ranking system – McIlroy reclaimed the spot while sitting out the tournament that week, only to see Spieth reclaim it a week later even though he missed the cut. Day, who probably wished there were more Majors to play after the PGA, eventually rose to no.1 on the back of some scintillating victories in the PGA Tour’s year-end play-offs. His new status was deserved, although in the larger comparison with his new rivals, his sole Major title trails McIlroy’s four and Spieth’s two.

It’s unfortunate that an Australian Open has just missed on bringing them together. Spieth returns to defend his title, again at The Australian, but McIlroy has finished a two-year turn of visits, and Day has shut down his year with the impending birth of his next child. What makes a potential rivalry between the three so compelling are the outlines, as neatly interlocking as rock-paper-scissors. Compared to McIlroy and Day, Spieth’s raw game isn’t quite as showy. He is middle-distance by tour standards, yet is a very good ball-striker, perhaps even sneaky-great, in the fashion of Jim Furyk. Spieth is undeniably a superb putter, surely the best ever to use the left-hand-low grip, and holes a ton of bombs – he led the tour in conversion rate from 4.5m to 7.5m, making more than a quarter of his putts where the tour average is closer to 12 percent. He plots his way around the course intelligently, collaborating very neatly with caddie Michael Greller, a former schoolteacher who began working with Spieth in his amateur days. If there’s a reason why Spieth doesn’t produce many “wow” moments on the course, it’s often because he doesn’t get himself into situations where he needs them.

But as the final round of the PGA in Wisconsin showed, claiming trophies sometimes comes down to who has the firepower. Playing together in the last group, Spieth couldn’t bridge the gap to Day, who won by three. Spieth later described it: “He wailed on it and it was a stripe show. It was really a clinic to watch. As he pulled driver late in the round, I kept having hope that maybe one of these drives he’ll miss and he’ll get a bad break ... You don't want to be in the position of hoping that.”

The drift of modern golf has been unkind to those who can’t play the power game.It’s hard to envision a long-term no.1 who doesn’t play that way. But Spieth has shown how it could. His career will be a test case for whether this most mental of sports will still tip to its most iron-minded exponent.

After the Masters, Spieth sounded the rallying cry for his generation: “Guys are coming out and winning quickly, and a lot ... That’s just kind of the mentality we all have as younger guys coming out now.” And that’s the thing about a model Major champ – his example is one that’s meant to be followed.

Related Articles

Lexus Encore elevates the Australian Open experience beyond the fairway

Australia still suits Lydia Hall

.jpg&h=172&w=306&c=1&s=1)