Tiger Woods' descent not unique in annals of his sport.

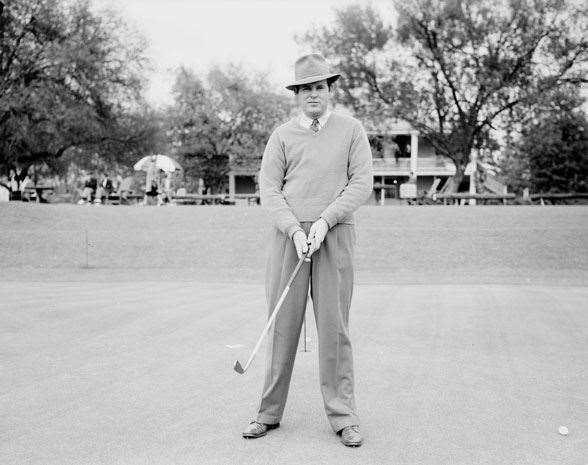

In the World Golf Hall of Fame in Florida, there’s a spot for Ralph Guldahl. He’s not exactly a first-rank name in the game’s history, but his playing record is worthy of the pantheon. This isn't the reason Guldahl is usually remembered, though, or how he has been commended to royal-and-ancient posterity. Indeed, his hall-of-fame bust should have yellow hazard lines drawn around it.

Guldahl, it bears repeating, was really good. Born in the charmed year-long stretch that produced Nelson, Snead and Hogan, the Dallas-raised Guldahl was better before any of them. At 18, he played in the 1930 US Open, won by a grand slammin’ Bobby Jones, and then won a US PGA Tour event the next year, becoming the last teen to pull off such a feat until Jordan Spieth, another Dallas kid, did it in 2013. By the consensus view, Guldahl was the dominant tournament golfer of the ’30s, particularly a four-year stretch at the end of the decade where he won back-to-back US Opens and three straight Western Opens, which was considered the second most prestigious title in American golf at the time. He was also a prominent contender at a glitzy new event, at Augusta National, that had been started in 1934.

He was the last US Open champion to win while wearing a necktie. Otherwise, his game didn’t radiate style. A tall man, his swing looked unorthodox, and his on-course manner inscrutable. Golf’s most venerable scribe, Bernard Darwin, noted of him: “Not an attractive player, unquestionably a powerful and resolute one ... capable of tremendous things at a pinch.” As Guldahl explained, “I was a full-blooded Norwegian,” which was a perfectly sound reason back in those days, it seems.

And yet, the first line of his Hall of Fame bio says it all: “Ralph Guldahl stands alone in golf history as the best player ever to suddenly and completely lose his game.” Guldahl had a deal to write an instructional book, one of the typical spoils afforded to golf’s champions. Groove Your Golf was pretty nifty for 1939 – it was a flip-book, a series of photos that could be made to look like a movie of Guldahl’s swing. But as the legend would have it, the process of deconstructing his technique for the book proved to be Guldahl’s undoing. While many careers were disrupted in the ensuing war years, Guldahl’s downturn in form was so severe that it forced him from the tour. He became golf’s classic cautionary tale of thinking becoming the enemy of doing. Instead of being a slick title, Groove Your Golf was an ironic taunt.

It wasn’t the book, of course. As former tour pro and golf history buff Mike Clayton says, neither Ian Baker-Finch nor David Duval wrote books. They were another pair of famed names afflicted by a similar phenomenon – that good golfers, even great ones, can lose their game in ways that seem utterly mystifying.

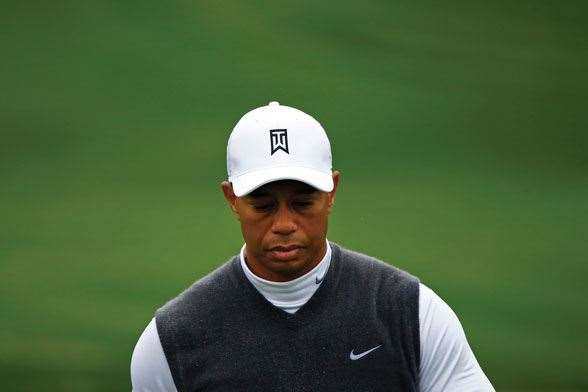

As the first Major of 2015 approaches, golf is gripped by the most unexpected Guldahl-like fall yet witnessed. Tiger Woods, whose sporting skill once inspired comparisons to Mozart’s talent for music, has seen his game deteriorate to levels that previously would not have been thought possible. After a horror, injury-addled 2014 season, Woods returned to action in February in Phoenix, declaring himself healthy and progressing neatly under his new coaching arrangements, which had seen him break with instructor Sean Foley to go independent, with help from a “consultant”, Chris Como. A cameraman had accidentally knocked his tooth out at one of girlfriend Lindsey Vonn’s ski races, but otherwise he seemed upbeat. After grinding through the first round, Woods blew out the next day, shooting his worst round as a pro, 82, and finishing last for the first time in a PGA Tour tournament. Worse still was how hapless he looked while doing it. Woods was resigned post-round, trotting out his often-heard line about his technique being stuck “between patterns”, and he just had to go do the work.

The next week, however, the alert level went redder than his old Sunday shirts. After 12 holes of his opening round in San Diego, a hobbling Woods chose to withdraw, the third time in his last eight starts he’d been unable to finish. In explaining his woes, Woods introduced the term “deactivated glutes” into the golf lexicon, and while the medical detail was murky, the overall impression was unmistakable – he was still having problems relating to his back, the bane of all golfers. Before his next scheduled event in Florida, Woods had declared he was taking a break from the tour. His reason: his standard of play was “not acceptable for tournament golf”.

The gamut of reaction was uneasy. Tour peers found themselves facing questions about whether they were sorry for Woods. Former greats, who had long been effusive about the 14-time Major winner, tried to stay upbeat and politely offered pieces of shop-worn wisdom. Armchair psychologists of every stripe had a field day. At the height of Tiger mania just after the turn of the millennium, another of golf’s venerable writers, Dan Jenkins, postulated that the only things that could stop Woods were a bad back or a bad marriage. It was intended as a compliment, an acknowledgement that Woods’ abilities implied the inevitable. But as both problems took their toll on him, it now looked chillingly prescient.

The sport of golf is trying to find a way to deal. Not just in the commercial “will-folks-watch-without-Tiger” sense, but in a narrative sense. From the time he was breaking amateur records as a teen, there was a feeling around Woods that he could be the rare sporting phenom that actually lived up to the hype. Indeed, what made him so compelling to watch, even to non-golf fans, was the idea that one hell of an epic was unfolding in real time. There was going to be a future in which a veteran Tiger would collect Major no.19 to the roar of an appreciative crowd, paying proper acclaim to one of the toughest record chases in sports.

That scenario looks borderline impossible now. Instead of a climax to Tiger’s tale, golf has to ponder what to make of a long fade-out.

As it is for other athletes (and yes, golfers are), physical breakdown is a garden-variety cause of a dip in performance on the course. While golfers don’t run quite the same injury risks, footballers don’t have careers that stretch into their forties and fifties. Wear and tear can accumulate over a long period of time. Woods was responsible for bringing an overt brand of athleticism to modern golf, and seemed to take pride in his over-the-edge exertions in the gym. His former coach, Hank Haney, was mystified at how Woods would wear his injuries like a jock badge of honour.

Curiously, getting healthy has been as disruptive to golfing greatness as getting hurt. David Duval was notably heavyset when he reached the no.1 spot in April 1999, before embarking on a fitness regime that helped him drop 20kg, but also his world ranking to no.527 five years later. Johnny Miller is the classic example: after spending the ’76-77 offseason clearing trees on his property, the spindly Miller’s frame filled out, and his new muscles caused him to lose his remarkable precision with his irons. Club golfers everywhere got the message – don’t exercise.

There’s another common trigger for sudden golfing decline, one that has developed its own mystique. The causes of focal dystonia are still not well understood, but the condition doesn’t lack for a marketable name: the yips. The mere mention sends a shiver up the (bad) backs of golfers everywhere. A sudden, involuntary muscle spasm that strikes only during specific tasks – musicians are known to suffer from them too – is death on the fine motor control needed in golf.

The yips are best known for wreaking havoc on the greens, where simple-looking putts can turn into roulette. Many great players have suffered from them, including Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Tom Watson and Bernhard Langer. Miller attributed some of his downturn to a yippy stroke setting in after the ’76 Open Championship. Putting yips get plenty of attention, because they are the last detail that thwarts otherwise fine play. They can also be managed – Langer, most notably, has been able to cope and scheme around them over a long and consistent career.

While obviously not desirable, a tour golfer can survive the yips with the putter. Get them with chipping, or worse, the driver, and a tour golfer won’t be a tour golfer for much longer. Chipping yips cut short the career of Fox Sports commentator Brett Ogle, a terrific ball-striker who could no longer bring himself to compete with his short game looking the way it did. For all of Woods’ troubles over the last 12 months, the most disconcerting sight of all was his greenside play in Phoenix. One of the finest short-game exponents in golf history, the conjurer of the hole-out on the 16th at the 2005 Masters was reduced to bumping four-irons from the fringe.

Watching from afar, Haney declared it a case of the chipping yips. From his time coaching Woods, Haney came to a surprising insight – far from being the inexorable golfing destroyer he appeared to be, Woods could get nervous, most often before the opening tee shot of a big tournament. Even in his prime, the litany of bad first drives from Tiger was rather remarkable, and consistency with the longest club in his bag remained elusive. Haney, who built a chunk of his teaching on his own experience of dealing with the driver yips, wrote in his book The Big Miss that he could see the beginning of such a problem in Woods, even if he was unlikely to ever get them.

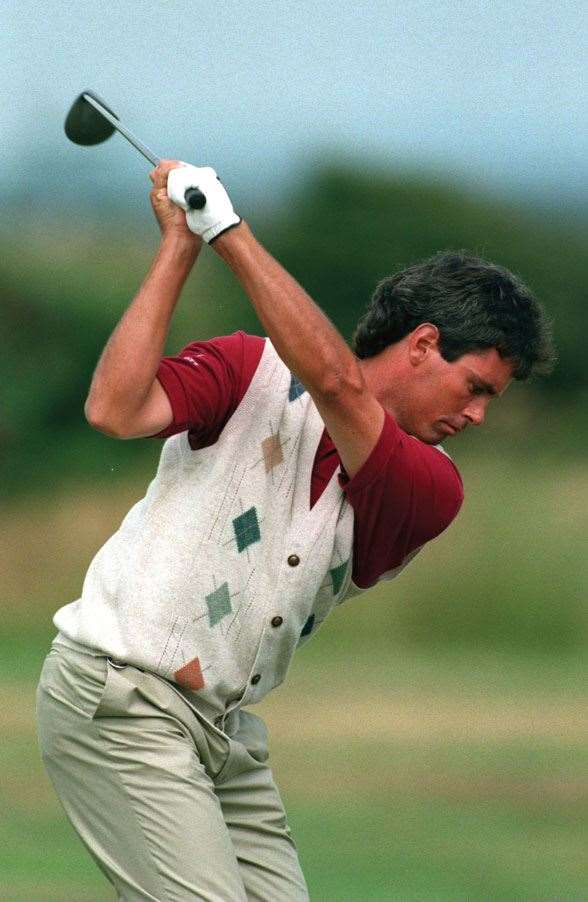

Truly, of all the yips, the ones with the driver are the fastest ticket off the tour. They led to the famous unravelling of Ian Baker-Finch, turning the ’91 Open champ into the player who couldn’t hit the widest fairway in golf, the first at St Andrews, at the ’95 Open. After shooting a 92 at the Open two years later, Baker-Finch retreated to the commentary box, unable to play yet wanting to stay connected to the tour. He’s become one of the better TV voices in the game, and he’s unflinchingly honest about his career spiral.

Baker-Finch was faced with a conundrum that often confronts the first-time Major winner. “I thought when I won, I reset my goals to win them all,” he told this magazine in an interview. “I thought, if I can win that one, there’s no reason why, if I just keep doing this and improving that, and if I can hit it a bit further ... You have to be careful you don’t get ahead of yourself.”

Champion golfers forever negotiate with the push-and-pull of trying to improve versus sticking to what got them there. Sometimes it works, but it can also lead to disarray. Baker-Finch tried to change his trusty left-to-right shot shape for a longer-going draw, but instead led to a situation that the pros dread – the two-way miss in both directions. IBF’s television colleague, Bobby Clampett, was a junior phenom, the poster boy for a school of physics-based swing theory detailed in the book The Golfing Machine, and encountered prompt success with a win and five runner-up finishes on tour before he turned 22. Clampett was a tinkerer by nature, and after spoiling a chance to win the ’82 Open, started taking advice from all quarters. His once-impressive technique became a muddle, posting only one second-place finish in his last ten seasons.

The saddest case of a great player technically adrift is surely Seve Ballesteros, mainly because no golfer defied the conventions of how to play quite like the Spanish legend. For the decade from 1979, he had been the world’s dominant golfer, collecting five Majors. As the ’90s rolled around, Ballesteros, who was still only in his early thirties, went about tightening his swing with a series of high-profile teachers.

“Players get spooked by other players,” Clayton says. “He got spooked by Faldo, probably. Seve was the best, and we were all in awe of what he did. Then Faldo went down that track of changing his swing and becoming the best player of his era, relentless as he stamped out one good shot after another. Seve saw that and thought, ‘That’s a whole lot easier way to play than the way I play. If I want to keep beating this guy, I’ve got to play more like him’.”

Clayton recalls a week he spent around Ballesteros in 1994, at the Benson and Hedges International Open in England. It was one of Seve’s last few wins, and despite playing well, a few of his choices riled his then-instructor, Mac O’Grady. “Seve played a young man’s game. It required great flair and skill. Mac told him that he couldn’t keep playing like that, you’re not 19 anymore.

“The inevitable happened with Mac, and they busted up. Seve never stuck with anyone, different teacher, different teacher, because he thought he knew best. And who’s to argue with that? But the problem is, you can’t go back. Why don’t you just go back to your old swing? You can’t, it’s gone.”

Seve, as many observers have noted, wasn’t wired for improvement. Woods, on the other hand, is the only golfer to have won Majors with three different swings. It’s fitting that he went to Stanford, because like a Silicon Valley product, he kept coming up with different versions – he’s up to Tiger 5.0, and reinventing his technique is what kept his golfing mind engaged. But in this current nadir, he just seems bogged down, a computer with too many programs running and some unhelpful bugs lingering. Baker-Finch sees a golfer who needs to free up.

“I don’t want to draw a comparison to an ability level when I mention my own troubles,” Baker-Finch said recently on Melbourne radio. “I would hit 50 perfect drives on the range, and snap-hook it off the first tee. He does exactly the same thing. At the first tee at Augusta every year, he hits it 100 yards off-line. Now, you can’t tell me that’s a bad back or swing flaw. It’s not the yips, it’s not a spasm. It’s a fear, and he has to overcome that fear and start feeling better about himself.”

The thought is unavoidable. If you draw the timeline, Tiger Woods’ golf-related issues can be traced back to that fateful night during Thanksgiving 2009. It seems too easy, overly facile, just tawdry – Guldahl was brought down by a book, Tiger by a tabloid paper. It’s a good story, but doesn’t hold up as a reason for bad golf.

But when it comes to losing it, the physical and mental factors aren’t as critical perhaps as the emotional ones. In 1981, Bill Rogers could rightly claim that he was the best golfer on the planet. He won seven times across the world that year, including the Open Championship, and was second in the US Open. He came to Australia later in the year, winning the NSW Open, then flying back home to the US, then returning to win the Australian Open at Victoria.

As a newly minted Major winner, Rogers was pushed by his management to cash in. Rogers, in an interview a couple of years back, said he took up the opportunities a little too enthusiastically and burnt himself out. His last win came in 1983, and five years of grinding later, he left the tour while he still had status.

“I know what Ian Baker-Finch went through, and David Duval,” he said. “The fact of the matter is, as sportsmen, we live on a very, very fine line. And from your folks’ [the media] standpoint, thinking and writing a lot about Tiger, you can see that anybody is vulnerable. And when you’re compromised off that great competitive edge, if you fall off of it, it can be quite a struggle.

“Tom Weiskopf once said when you’re playing good, you’ll never think you will play bad again. And the reverse: when you’re playing bad, you never think you will play good again. It’s kind of that-type deal.”

Rogers, a native of Texas like Guldahl, chose family life, and also found religion. “At this stage of the game, I understand a lot better for what it was,” he reflected. “Part of the reason I went home is, God had a different calling for me, entering a faith journey, looking back and understanding from a worldly perspective how I was driven. I found my identity in how I was doing. And if I was doing well, I was high as high can get. The thing about that is, people are always reminding you how great you are. When you’re doing well, everybody has questions, and you’ve all the answers and that’s a powerful place to be – it’s kind of a drug, if you want to look at it.”

Duval, one of the more thoughtful golfers out there, once admitted to an “is-that-all-there-is?” moment upon becoming a Major champion. Long regarded as dour and single-minded as he rose to the top of the game, Duval became more personable, married a single mother-of-three, and saw his life off the course improve even as his golf went in the other direction.

Speaking to Reuters recently about Woods, Duval noted: “Through everything I went through I realised the most important thing to protect as a golfer is your confidence and your arrogance, for want of a better word. You need to have 100 percent belief in what you’re doing and think you’re bulletproof out there.”

This is where the fire hydrant hits. Woods went through one of the more brutal public shamings to be found in this media age. On the course, what was once total support from the gallery became much more equivocal. That imperious manner in which Tiger carried himself became a little less convincing. His own self-image was dented, and the game of golf will deal out enough humiliations to turn that dent into a hole. Woods has played well at times post-scandal, including a player-of-the-year-type season in 2013. But the doubts – his health, the loose shots, the weekend letdowns at Majors – have continued to accumulate.

It was once said of Seve that his greatest asset was a single-minded conviction that he was the best player on the course. As Clayton drily notes, the best players believe it because their shots provide the evidence. “It goes the other way too,” he says. “Seve saw the evidence of decline, with the shots he was hitting. You lose that self-belief, and you can lose it quickly, in a single shot sometimes. Shit, what’s that? I’ve never seen that shot before.”

So much of being a great golfer is not looking like a bad one. For a top player, with further to fall, the fear of being embarrassed on the course can become palpable. “Tiger has just seen the evidence,” Clayton adds. “Can’t hit the fairway, can’t chip it on the green. The evidence is stark. What happens now? Can I be bothered to get it back, or do I walk away?”

Johnny Miller, who was one of the rare ones to kind-of get his game back after it dipped, once identified two types of tour golfer: the ones who loved to play so much that they woke up looking for their clubs, and the ones who loved the game as a way to compete. It’s part of Woods’ enigmatic quality that he hasn’t resolved which type he is – while he has aspects of golf junkie to him, he’s always maintained he’ll only play if he’s competitive. “If I can’t, why tee it up?” he said at his year-end event in 2013. “There’s going to come a point in time where I just can’t do it anymore ... I’m aways away from that moment in my sport, but when that day happens I’ll make a decision and that’s it.”

Early this year, golf lost another Hall of Famer, its oldest living Major champ, when Kel Nagle died at 94. The Open winner had a remarkable career, and as Clayton reminisced in an obit about playing with the near 60-year-old Nagle, was one of those players who was still competitive in his later years. “Who played the game more simply than Kel Nagle? Or Julius Boros? Those guys who played with such beautiful natural rhythm. They’re the guys who don’t lose it.”

As Augusta rolls around once more, we’re a year away from the anniversary of perhaps the greatest late-career golfing achievement. When 46-year-old Jack Nicklaus won the ’86 Masters, it became the fitting emblem for a champion who maintained a durable excellence over a quarter-century.

Nicklaus’ record of 18 professional Majors has so defined Woods’ career that it led to the assumption that his career arc would track the Golden Bear’s long haul. Instead, Woods’ brilliance might have shone a little brighter, but also burned the fuel more quickly.

One of golf’s particularities among sports is that its champions last, and there’s almost an expectation that they’ll always be around the game. The Masters taps into this sentiment with its lifetime exemption for past winners, a circle of honoured elders who get a place in the Majors’ most exclusive field, even if their prime is well past. In 2002, there was minor controversy when the club tried to impose an age limit on the lifetime exemption. They were forced to back down a year later, and in 2005, Billy Casper, another recently deceased Hall of Famer, shot an avert-your-eyes 106. But no one would dare keep an old Masters champ away.

One of them, back in the day, was Ralph Guldahl. After consecutive runner-up finishes at the Masters, he finally claimed the green jacket in 1939, his last Major before the slide set in. He did return to make a handful of ceremonial appearances, his last in 1973. In an interview a few years later, Guldahl disputed that the book had been the problem. He admitted that his competitive hunger had simply been exhausted, and was never too great to begin with.

He had quit golf once before, after missing a putt for a play-off at the 1933 US Open. Guldahl took up selling used cars, then worked as a carpenter for Warner Bros, and it was only the intervention and backing of the movie studio bosses that convinced him to make his successful return to golf. But the grind eventually wore him down. “I never did have a tremendous desire to win,” he said in 1979, eight years before his death. “And under the conditions that today’s professionals play, I would be quicker to say ‘the hell with it’ than I did then.”

- By Jeff Centenera (@jeffcent1001)

Related Articles

Hero World Challenge field spotlights Australian Open hurdle and OWGR prospects

Heartbreak for Aussies at history-making Asia-Pacific Amateur