Recent major course renovations at some big-name clubs in Australia have come under the watchful eye of experienced course architects and have received rave reviews. The clubs have benefitted from trusting an expert eye, reminding once again of the potential pitfalls DIY course changes, or lack thereof, can cause.

Golf Australia magazine Architecture Editor Mike Clayton’s article ‘Beauty and fun in width’ posted on the Golf Australia website in September was totally on point with regard to some of the challenges that lie ahead in rectifying the well-intentioned errors of the past that afflict many golf courses in Australia and no doubt, other parts of the world.

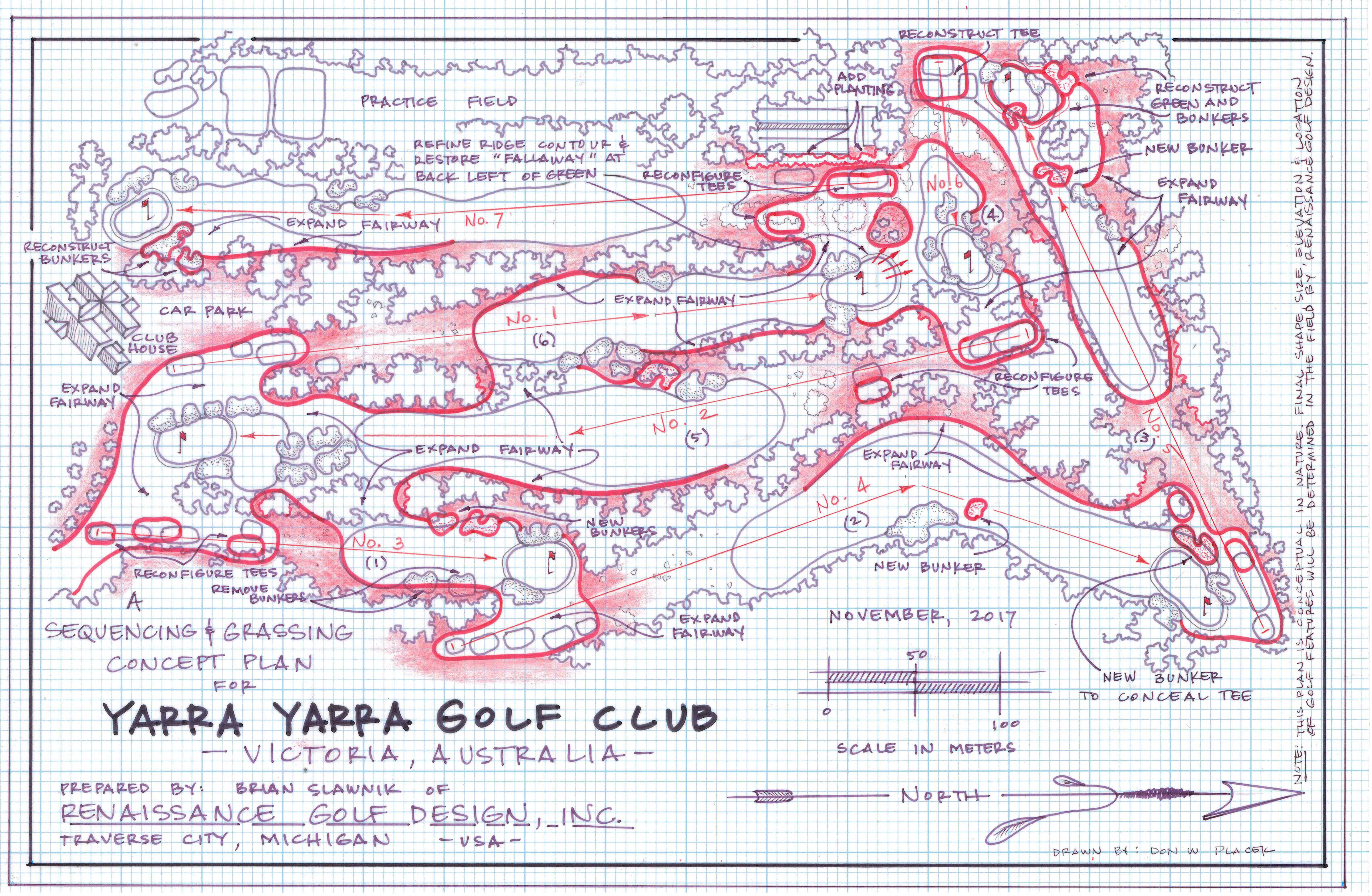

Clayton cites the recent renovation at Yarra Yarra on the Melbourne Sandbelt as a case in point.

“Along with almost every other club on the Sandbelt, the early members at Yarra Yarra made the quite predictable – understandable even – mistake of importing both European and “native” vegetation on to the largely treeless original course.”

“The mistake was a failure to understand the indigenous plants – the ones which over centuries had best adapted to the site – were the only way to plant out a golf course and have it feel completely natural. Ask the critics if a golf course should feel “natural”, and the answer will be 100 percent “yes”.

He also notes that the Englishman who imported the first rabbits to this country might like his time over in hindsight, and the same could be applied to the introduction of lantana and the cane toad. All well-meaning actions but with subsequently dire consequences in their respective cases.

In Australia’s catalogue of 1,500+ golf courses, I would suggest a high proportion can point to this malaise affecting them to some extent too. As the saying goes however, those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

Unlike Clayton, as a golf writer with no vested interest in the course architecture business whatsoever, I’ll do what he couldn’t which is to plead, implore, even beg, any golf club with an interest and the means to make course improvements to engage the expertise of an accredited golf course architect before taking any expensive and potentially business-affecting course of action.

I emphasise ‘the means’ because in no way am I being critical of those who are not undertaking course improvements where they should as a routine part of their business plan. I’m sure nothing would please them more but few clubs have a considerable war chest of funds available to invest in their course.

The financial constraints are very real, even if the cost of some considered and impactful renovations might not be as high as many clubs might anticipate, with a number of architects around Australia without the profile of Clayton or overseas big names like Tom Doak or Gil Hanse more than willing to ply their trade.

Over the decades, the honourable course of action from volunteer committees has been to look ’in house’ to do as much as possible, using the skills, talents and business networks available from within the committee and membership. In many aspects of the business of running a club, this collegiate approach has been at the heart of most clubs’ culture and sustainability and is to be applauded.

The club where I started as a junior had a close relationship with local heavy industry and mining sector so quite obviously, access to engineering skills, drainage pipes and other equipment were able to be sourced periodically. Despite this and as Clayton details in the Yarra example, various committees of equally well-meaning people with unquestionable skills in their chosen fields of business, progressively executed on decisions that had longer-term repercussions for the club’s primary product – the golf course.

While some good moves were made, some of the adverse decisions included how course drainage was laid out, poorly conceived tree planting strategies by ‘green thumb garden guru’ members with time on their hands, tee and bunker removal and/or creation – all done in house without much by way of consultation with an expert in the course design field.

Compounding the issue was prevailing support for the notion that ‘harder is better’, which in practical terms meant that an ever-increasing prevalence of overhanging limbs and tangled vegetation just off the fairway were viewed by some as necessary defences against the better player and the rampant strides of technology.

Only the other day, I played a course that will remain unnamed with some basic bunkering on the ‘outside’ of the left to right dogleg on a par-four. To the right of the fairway, choking trees were planted so close together that the ground underneath was in a permanent state of shade. As if that side was not impenetrable enough for an angry golfer and their mashie, a deviously positioned pond not visible from the tee lurked at the elbow of the dogleg.

On the left side, the bunkers was actually positioned directly in front of another hidden pond a few steps beyond. One hazard protecting golf balls from going in another (hidden) hazard.

Suspecting that no golf course architect worth his salt would have presided over this, it was suggested that as a consequence of complaints that too many tee shots were going into the pond, slowing up play with searches and ball drops, the bunkers were installed to stop balls going into the pond.

Examples of this sort of decision making I’m sure can be replicated the country over and result in a patchwork quilt of course design anomalies that in some cases (but not all), would require vast effort and resources to address. No doubt, those complaining members and the presiding committee members have long since moved on and ‘the current generation of committees and consulting architects are left to deal with these mis-steps of the past’, as Clayton suggests.

Contemplating doing something at all about these issues is the first step for any committee or private course owner to face. Quite often, this is the toughest step in the change cycle as they juggle the financial investment, logistical and cultural imposts that making a decision to ‘change’ presents in life. Again, a ‘go’ decision is to be applauded in any economic climate and in my opinion, there are few more exciting things to hear about in the game than news that a club is investing in their major product and not simply tacking on a gaming room.

Once a decision to pursue some thinking on, or to proceed with, a course improvement project is made however, surely the best form of due diligence for the long-term future of the golf club, its role as a place of employment in the community and its ongoing attraction to others interested in spending their time and money with you (memberships, social play), is to engage a course architect to provide a strategic plan – devoid of the emotion and local history that so often cripples good ‘in house’ decision making – for the years and decades ahead?

I would guarantee that not one member of a current day golf club committee or private course owner would buy a house with their own money without ‘first’ seeking a pest and building inspection from a qualified expert in the field.

Applying that same due diligence and fiscal responsibility to course improvement projects – small, medium or large – heightens the prospect of a positive upside to a golf club’s business, not to mention the standard and quality of the golf offering in this country well into the future.

Related Articles

Review: Yering Meadows Golf Club

Nick Voke, thriving by doing it differently