Former champion Geoff Ogilvy says the extensively renovated Pinehurst No.2 course will provide a very different US Open championship when it tees off next week.

The thing about the US Open is that you always know what you’re going to get. The course will be really long, as will the rough. The fairways will be really narrow. The greens will be firm. And whenever you miss a shot by even a little bit, the resulting penalty will be severe. That, like it or not, is the typical blueprint for America’s national championship.

Having said all that, what might be called the “Mike Davis era” (the USGA’s executive director who is responsible for course set-up at the US Open), has seen the introduction of some variety on that basic theme. The past few years have been a little more interesting. We’ve had short par-4s, some of them driveable. We’ve seen the tees at par-3s move around on each of the four days. And there have even been what America rather perversely calls “chipping areas”, patches of short grass around the greens.

Still, although things have been a little different in places, the basic philosophy has not changed. Things are fine as long as you are hitting perfect shots. But as soon as you hit one that is less than ideal, you are going to have a really tough time making par. Davis may have occasionally moved away from the traditional method of punishment, but anything less than perfection has still seen even the most imaginative players reduced to chipping out.

Every year, too, the USGA claims they don’t care what the winning score turns out to be. Yet every year it is right around level-par. So, despite what they say, it feels like they care! Don’t get me wrong, though. I don’t mind a really hard test. But the US Open is mentally intimidating as much as it is physically difficult. Even when you play well – as I did in 2006 when I won at Winged Foot – you still walk off not really sure what just happened.

Taking the result out of the equation, if I had been asked right after I left the 18th green eight years ago how I had played, I’m not sure I would have known what to say. Yes, I knew I had done well. But had I played well? I’m still not sure to be honest. Although I can legitimately claim that I did perform close to the best of my ability – my name on the trophy proves that – it never felt like I was playing well. Because I was struggling so often to make pars.

The US Open is like that for everyone, of course. Every competitor has to get up-and-down for par maybe nine times a day if he wants to post a good score. When that is the case in a regular tournament, you know you are not playing well at all. So our equilibrium is upset, the score on the board not really telling us everything about the quality of our play. If I didn’t have the rest of the field to measure myself against, I really would have no idea.

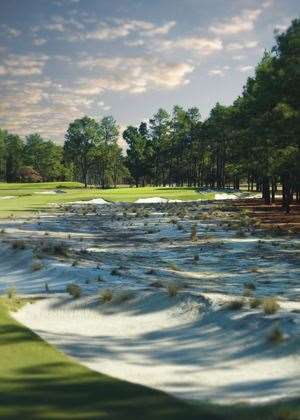

This year, however, has the potential to be a bit different from the norm. Par will still be a good score over 72 holes, but the set-up of Pinehurst No.2 – especially the lack of rough and the width of the fairways – is going to provide an unusual US Open test. Missing the fairway isn’t going to happen quite so often and, if I do spray one off the tee, I’m going to be faced with a shot from pine straw or a sand-covered waste area. Sometimes I’ll have a perfect lie for the recovery shot; other times I’ll be in a footprint and having to chip out; and the rest of the time I’ll have something in between those two extremes. I like the randomness of that equation.

In turn, I’m going to have to adopt a very different mentality from what is normally required in the US Open. Unlike some of the leading courses nowadays, Pinehurst No.2 is a lot more about position than out-and-out distance. A bad lie on the correct side of the fairway is going to be better than a good lie on the wrong side of the fairway. Again, I like that scenario.

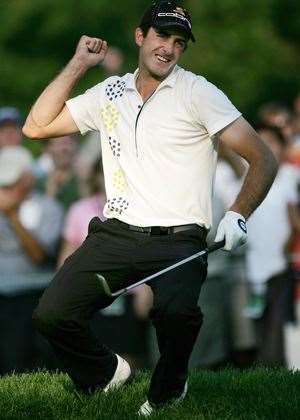

When Geoff Ogilvy chipped in en route to winning the 2006 US Open, pars were a premium due to the high rough. PHOTO: Getty Images

When Geoff Ogilvy chipped in en route to winning the 2006 US Open, pars were a premium due to the high rough. PHOTO: Getty ImagesIn at least one respect, Pinehurst is straightforward. If I keep driving my ball into the correct spots, the second shots will be more obvious. That’s so important. The greens play really ‘small’ if you approach them from the wrong places. They’re all ‘up in the air’ and they all roll off on the sides. Even after 18 perfect tee shots, hitting 12 to 13 greens in regulation is still a pretty amazing feat.

For that reason it’s so important for the correct spots to be available for the tee-shots. In 2005 – the last time the US Open visited – they were covered in long grass. This time, I’m hoping that the ideal driving areas will be accessible, albeit close to the sandy waste areas. Chasing perfection should involve at least some risk, just as it does at the Masters every year.

My one fear is that, in order to keep the scores up, the USGA might succumb to temptation and take refuge in some overly severe pin positions. That is definitely a trend in modern Tour golf. Over the course of my relatively short professional career, pin positions have gradually become markedly more difficult. Almost every week on Tour I see pins almost on the edges of putting surfaces, often right next to water. And at the four majors that penal philosophy is even more prevalent.

Given the lack of rough, I’m sure the USGA will be concerned about the scoring. So I won’t be surprised if all 18 pins are really tough on day one. They won’t want anyone ‘running away’ from the field. Only if everyone really struggles can I see that level of difficulty being modified.

The irony is that, with every pin placed in the middle of every green, Pinehurst is still an incredibly difficult test of golf. If the USGA gave us 72 ‘easy’ pins, I still don’t think anyone would reach double-digits under par. The putting surfaces may look big, but they play very small. The outside ten feet or so of every green is unusable because balls run off.

The Pinehurst pin positions also have the ability to fool the unwary. The pin sheet may

tell you the hole is cut, say, ten feet from the edge, but the reality is the actual number is two feet. Miss by that much and the slope will carry the ball the rest of the way and, inevitably, well off the green.

Anyway, despite my reservations, I do think the USGA deserves a lot of credit for taking the US Open to a restored Pinehurst No.2. It’s not easy to find new and more interesting ways to make the event incredibly difficult – if that is not an oxymoron. It’s heartening, too, to see they haven’t just resorted to the age-old formula and simply covered the course in rough. At least for that, I suspect, Mike Davis and his team will receive the enduring gratitude of everyone in the field.

Related Articles

Feature Story: The battle of the Peninsulas

The NZ PGA Championship and the beating heart of Kiwi golf