A report has examined the problem of pace of play at clubs around Australia. the report looks at the causes, the impact and how round times can be improved.

BY BRENDAN JAMES

Slow play … every golfer hates it, but there are few among those playing 1.2 million rounds of golf annually in this country that would put their hand up to confess being a slow golfer.

Time, in this day and age, has become a treasured thing that most of us complain we don’t have enough of. So, when it takes more than four, or even five, hours to play an 18-hole round of golf, it puts the game on the nose as far as attracting new people into the sport. Then there are the established club golfers who are finding it harder to devote enough time to fit a round in on a regular basis.

Pace of play is the basis of a report commissioned by Golf Australia (GA), which is aiming to get a better understanding of the issue. GA chose to undertake a survey of club administrators across the country to round out the information being collated in a worldwide study by the R& A of individual golfers. The results of that R&A survey, to be covered in the June issue of Golf Australia magazine, looks at the issue from the golfer’s perspective.

Golf Australia’s Pace of Play Report sought to discover more information around five key points:

- The true extent of the pace of play issue in golf;

- An understanding of all of the causes, from a club administrator’s perspective;

- The degree of importance the industry attaches to trying to improve pace of play;

- What impact is slow play having on golf club financial outcomes; and

- What are the most effective strategies to improve pace of play.

Golf Business Advisory Services (GBAS) developed a 24-question survey, which was distributed to 1,600 golf clubs throughout Australia. Approximately 150,000 playing members – about 40 percent of Australia’s affiliated playing members – were represented by the 312 club administrators that responded to the survey. To read a full copy of the report, CLICK HERE

Golf Business Advisory Services (GBAS) developed a 24-question survey, which was distributed to 1,600 golf clubs throughout Australia. Approximately 150,000 playing members – about 40 percent of Australia’s affiliated playing members – were represented by the 312 club administrators that responded to the survey. To read a full copy of the report, CLICK HERE

THE CAUSE?

Of those clubs that responded in this survey, only 25 percent of them had a serious concern regarding pace of play in male events, with only 16 percent sharing a similar view with female events.

But the GA study further established that bigger clubs with a high number of members had a greater concern about pace of play than those clubs with a smaller membership. Bigger clubs also host more competition rounds, adding to the problem of pace of play.

In addition to this, clubs with a more difficult golf course (measured by the respective course’s slope rating) have a higher concern about pace of play issues than easier courses.

However, club administrators overwhelmingly believe that “behavioural factors within the control of the individual golfer” are largely responsible for pace of play issues, rather than club operational factors like course set-up.

“Examples include golfers not being ready to play when it is their turn, pre-shot routines, not calling groups through etc,” the report says. “This suggests there are solutions readily available to improve pace of play issues but they are not being implemented due to an alternate focus on the behavioural factors of individual golfers.”

Successfully educating players to pick up the pace – in comparison with course set-up or a club’s operations – is not an easy task to change in the long term.

“The discussion around pace of play therefore becomes a question as to what is most important,” the report says.

Marking your card on the green not only holds up the group behind you but adds to the time of your own round. Clubs promoting ‘ready golf ‘ are keen on eradicating this in a bid to improve the pace of play.

Marking your card on the green not only holds up the group behind you but adds to the time of your own round. Clubs promoting ‘ready golf ‘ are keen on eradicating this in a bid to improve the pace of play.“Is it the way in which the product is presented to the customer or is it the manner in which the customer is consuming the product?”

Whilst the concept of ready golf addresses the customer and their behaviour, and those who have adopted it have achieved some improved outcomes, clubs with concerns about slow play, the report suggests “should be equally encouraged to also focus on how they are presenting the product.”

With club golf in Australia revolving around competition play, the various formats of competitions were examined. It was established that different scoring methods certainly impact the time taken to play a round, with Par competitions taking the least time to play. Interestingly, clubs with the highest concerns about slow play only have 12 percent of their competition schedule devoted to Par events.

The overwhelming theme coming from respondent clubs is that pace of play issues can be easily attributed to the behaviours of golfers, rather than factors within the club’s control.

In fact, seven of the top-10 reported influences on pace of play can be attributed to the behavioural factors of golfers. The three remaining factors – age profile, limited golf skill and a visiting golfer’s lack of course knowledge –are all limitations of the individual golfer.

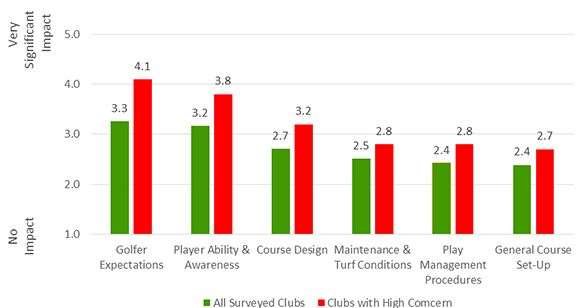

“It is evident from that graph that player behaviour reasons account for the top eight issues proffered by golfers. Consistent with the broader global findings, it is clear that the significance of the contributing course management factors are not well understood,” the report says.

“This finding also suggests that where the national and international governing bodies have not made a concerted effort to raise awareness of the impact on pace of play of various service provider actions, it is unreasonable to expect these implications to be intuitively understood.

“Interestingly within the North American market the most frequently cited cause by the consumer was players using tees which are too difficult for them. This finding indicates that the USGA’s “Tee It Forward” campaign is of particular relevance within that region. Such a campaign indicates that administration led initiatives can be effective and, in the North American case, successfully filter through to golfers in that market.”

There are no factors relating to course set-up, golf operations or the nature of the golf course or conditions are considered to be in the top-10 factors influencing pace of play.

However, five of the top-10 strategies – those being ‘golfers not ready to play’, ‘pre-shot routines’, ‘marking cards when should be teeing off’, ‘golfers overestimating their length’ and ‘unnecessary marking on greens’ – are factors which the promotion of ‘Ready Golf’ in golf clubs seeks to alleviate.

THE IMPACT

Respondents to the GA study were asked to rate the negative impacts that pace of play has on certain indicators that are often synonymous with a well-performing golf club. These factors included maintaining high member satisfaction; an ability to maximise golfers’ opportunity for post-round spending/socialising; the impact of slow member play on available remaining time for social golf and subsequent green fee revenue generation; and, member retention and attraction.

Generally, club administrators believe pace of play is having a limited impact on club performance. However, those clubs where pace of play is an ongoing problem, there was a concern about keeping members satisfied.

The study highlighted that club administrators considered the impact of slow play, in member competition rounds, on their ability to accommodate green fee/social golfers after those rounds was only of average concern.

But the report notes that being able to provide times for social golf and the subsequent green fee revenue generation “should be highlighted due to its compounding nature”.

“If slow play was to cause one less four-ball slot being available for social play each weekend, if paying $40 per round, this lost time slot equates to approximately $8,300 in lost revenue per annum,” the report said. “Two lost slots equates to $16,600, and four slots exceeds $30,000. Such revenue, let alone profit, is not always immediately replaceable.”

It is not hard to assume that a short fall in green fee revenue, perhaps caused by slow play, might force club administrators and golf club boards to sign off on increases to member’s annual fees.

Thinning out roughs does add increase the pace of play as players don’s spend time looking for their ball.

Thinning out roughs does add increase the pace of play as players don’s spend time looking for their ball.SPEEDING UP PLAY

Based on responses provided to GA, there are many actions club administrators are not taking to address pace of play, particularly at clubs where concern for pace of play exists. While the promotion of ‘ready golf’ is widespread and four other measures have been tried, all other measures listed in the survey – including using a course marshall, slowing green speeds, increasing tee time intervals and threatening restrictions for repeat slow players – have been implemented by less than half of surveyed clubs, including those with a high concern for pace of play.

Clubs where there is a high concern about slow play, have implemented several actions to improve the speed of play including the promotion of ‘ready golf’ (84 percent), thinning roughs (73 percent), penalising slow play offenders (76 percent), clearing out areas adjacent to playing areas (62 percent) and using friendlier flag positions (64 percent).

WHAT IS READY GOLF?

It is exactly what it says…being ready to play as soon as possible.

Examples of ready golf include:

- Hitting a shot if the person furthest away is faced with a challenging shot and is taking time to assess their options;

- Shorter hitters playing first off the tee;

- Putting out, even if it means standing on or close to someone else’s line;

- Hitting a tee shot if the person with the honour is delayed in being ready to take their shot;

- Hitting a shot if the person who’s just played from a bunker is still furthest from the hole but is delayed due to raking; and

- Marking scores after hitting off on the next hole.

Implementing these actions separately or collectively will improve the pace of play.

Of the clubs who have promoted ‘ready golf’, 94 percent have enjoyed some degree of success with 25 percent reporting ‘satisfying success.’

Related Articles

The NZ PGA Championship and the beating heart of Kiwi golf

Column: LIV’s star exodus could be catastrophic, except in Adelaide

Nick Voke, thriving by doing it differently

Latest News

"Fuel to the fire": Smylie sets sights on major leap

Your week on the box: Golf tournament TV times

Aussies aided by inside knowledge at Women's Amateur Asia-Pacific

Most Read

RANKING: Australia's Top-100 Courses for 2026

Lexus Encore elevates the Australian Open experience beyond the fairway

Next big thing, sure. But world's best? From LIV league? Jury is out